The “I’m Not a Racist” Deep Racist (Then and Now)

Not everyone wears a white hood.

And you do not have to be White to be a deep racist.

When people imagine racism, they often picture overt villains—KKK robes, Nazi insignia, explicit slurs, or cartoonish hatred. That framing is convenient. It allows many people to exempt themselves from scrutiny while continuing to participate in systems and behaviors that are profoundly racist in effect.

Deep racism does not require spectacle. It survives through ethical evasion, selective humanity, and the deliberate toleration—or protection—of cruelty inflicted on Black people.

What Deep Racism Actually Is

Deep racism is not merely “not caring” about Black lives. On some level, many people do care. The issue is what they are willing to overlook, excuse, delay, or rationalize when harm is inflicted on a Black person—especially by someone they know, benefit from, or identify with.

You are engaging in deep racism when you:

Overshadow ethics to allow a Black person to be unjustly, immorally, or violently harmed by another Black person.

Justify or minimize abuse because confronting it would disrupt your comfort, image, alliances, or access.

Attempt to “balance” your complicity by supporting another Black person elsewhere, as if moral accounting can offset tolerated cruelty.

This is not about failing to fix the world or not doing enough for every cause. That accusation is often manipulative and inaccurate. Deep racism is about intentional choices—about where you draw ethical lines and when you decide they don’t matter.

A Historical Prototype: John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon (1723–1794)—a signer of the Declaration of Independence, Presbyterian minister, and president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University)—offers a clear historical example of deep racism in action.

Witherspoon enslaved people. At the same time, he assisted freemen, invested in religious education for certain enslaved individuals, and spoke the language of liberty and equality common to the Revolutionary era. This combination is often used to portray him as “complex” or morally conflicted.

But complexity does not absolve cruelty. In Witherspoon’s case, it exposes how racism persists through selective morality.

The Horse Argument: Codifying Dehumanization

During debates over Article XI of the Articles of Confederation, Witherspoon sided with Southern states and adamantly opposed the taxation of enslaved people. His reasoning was explicit:

“It has been objected that negroes eat the food of freemen & therefore should be taxed. Horses also eat the food of freemen; therefore they also should be taxed.”

This was not an offhand remark. It was a legal and philosophical maneuver.

By equating enslaved people with horses, Witherspoon:

Denied their humanity in law and policy

Reduced them to consumptive property

Framed them as economic burdens rather than rights-bearing humans

This is deep racism in its most disciplined form: the use of rational-sounding logic to erase human dignity.

Selective Humanity Is Not Justice

Defenders often note that Witherspoon invested in the religious education of individuals such as Jamie Montgomery, John Quamine, Bristol Yamma, and John Chavis. These actions are sometimes offered as evidence that he did not truly view enslaved people as equivalent to animals.

But that is precisely the point.

Witherspoon could recognize intellect, spirituality, or usefulness in individual Black people while still supporting a system that denied Black humanity at the structural level. His personal gestures did not challenge the institution of slavery; they existed comfortably alongside it.

Selective compassion is not justice. It is a mechanism that allows oppression to continue while preserving the oppressor’s self-image.

Delayed Abolition as Moral Laundering

In 1790, Witherspoon chaired a New Jersey committee tasked with considering abolition. The committee recommended taking no action, claiming slavery was already dying out and would end within twenty-eight years.

That recommendation mattered.

Because of it:

Slavery continued largely undisturbed in New Jersey

The state delayed meaningful action until 1804

Enslavement persisted in New Jersey until the end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865

This was not neutrality. It was ethical deferral—a choice to prioritize institutional comfort and political calm over immediate human freedom.

Calling this anything other than racism misunderstands how racism actually functions.

The Modern Parallel

Deep racism today follows the same pattern:

Acknowledge harm in theory, but block accountability in practice

Express concern, but protect the abuser

Invoke gradualism, complexity, or “both sides” to justify inaction

Redirect attention to another Black person or cause to offset deserved criticism

This is not balance. It is moral laundering.

And it is racist because it permits Black suffering when confronting it would cost something.

What Accountability Actually Requires

Deep racism is not an immutable identity. It is a behavior.

People can amend their actions—but not by rewriting history, hiding behind intentions, or pointing to selective good deeds. Accountability begins with refusing to justify inhumane treatment of Black people under any guise: not tradition, not familiarity, not inconvenience, not loyalty, and not optics.

You do not have to be perfect.

But you must be honest.

And you must stop pretending that cruelty tolerated, delayed, or excused is anything other than what it is.

How This Pattern Has Been Abusive to Me

The same logic that excused, delayed, or rationalized harm in the past has been directed at me in the present. What I describe here reflects my lived experience and allegations, supported by documentation I have preserved, and presented to illustrate how deep racism functions when it moves from moral failure into coordinated abuse.

I have not only been harmed through silence or delay, but through active participation by individuals and institutions who chose to side with my abusers. This participation has included the following patterns:

Stalking and surveillance: I experienced repeated monitoring and following behaviors designed to intimidate, unsettle, and restrict my movement. These acts functioned as psychological pressure rather than isolated incidents.

Poisoning and food tainting: I experienced food and beverage contamination consistent with intentional tampering. These incidents were dismissed or minimized, compounding the harm and leaving me vulnerable to further exposure.

Triangulation and information laundering: Personal information about me was circulated, reframed, and weaponized through third parties. This allowed false narratives to travel while obscuring their origin and insulating those responsible.

Defamation and character assassination: False statements were made about my behavior, credibility, and mental state. These lies were repeated across contexts until they were treated as truth, undermining my safety, reputation, and access to help.

Financing and rewarding abuse: My abusers were materially supported—financially or through access and protection—while I was deprived of resources, credibility, and recourse.

Law‑enforcement and carceral misuse: I was subjected to arrest, incarceration, and detainment not as protection, but as punishment for resisting harm or seeking accountability. These actions mirrored historical patterns where Black resistance is reframed as deviance.

Medical abuse and gaslighting: My physical and psychological symptoms were dismissed, mischaracterized, or used against me. Rather than care, I encountered coercion, disbelief, and pathologization, which further dehumanized me.

Exploitation of suffering: My pain and circumstances were treated as material—for gossip, spectacle, leverage, or institutional convenience—rather than as urgent harm requiring intervention.

This was not a series of misunderstandings. It was a pattern of coordinated dehumanization.

The ethical inversion was consistent: those inflicting harm were protected, normalized, or excused, while my attempts to assert boundaries or document abuse were framed as instability, hostility, or misconduct. Delay was called caution. Inaction was called neutrality. Punishment was called procedure.

This is how deep racism operates in real time—not only by denying humanity in theory, but by mobilizing systems to enforce that denial. It decides whose suffering is actionable, whose voice is credible, and whose life can be destabilized without consequence.

I include this section not to solicit sympathy, but to demonstrate continuity: from historical selective humanity to modern institutional participation. The same moral logic persists, and its effects are not abstract. They are lived.

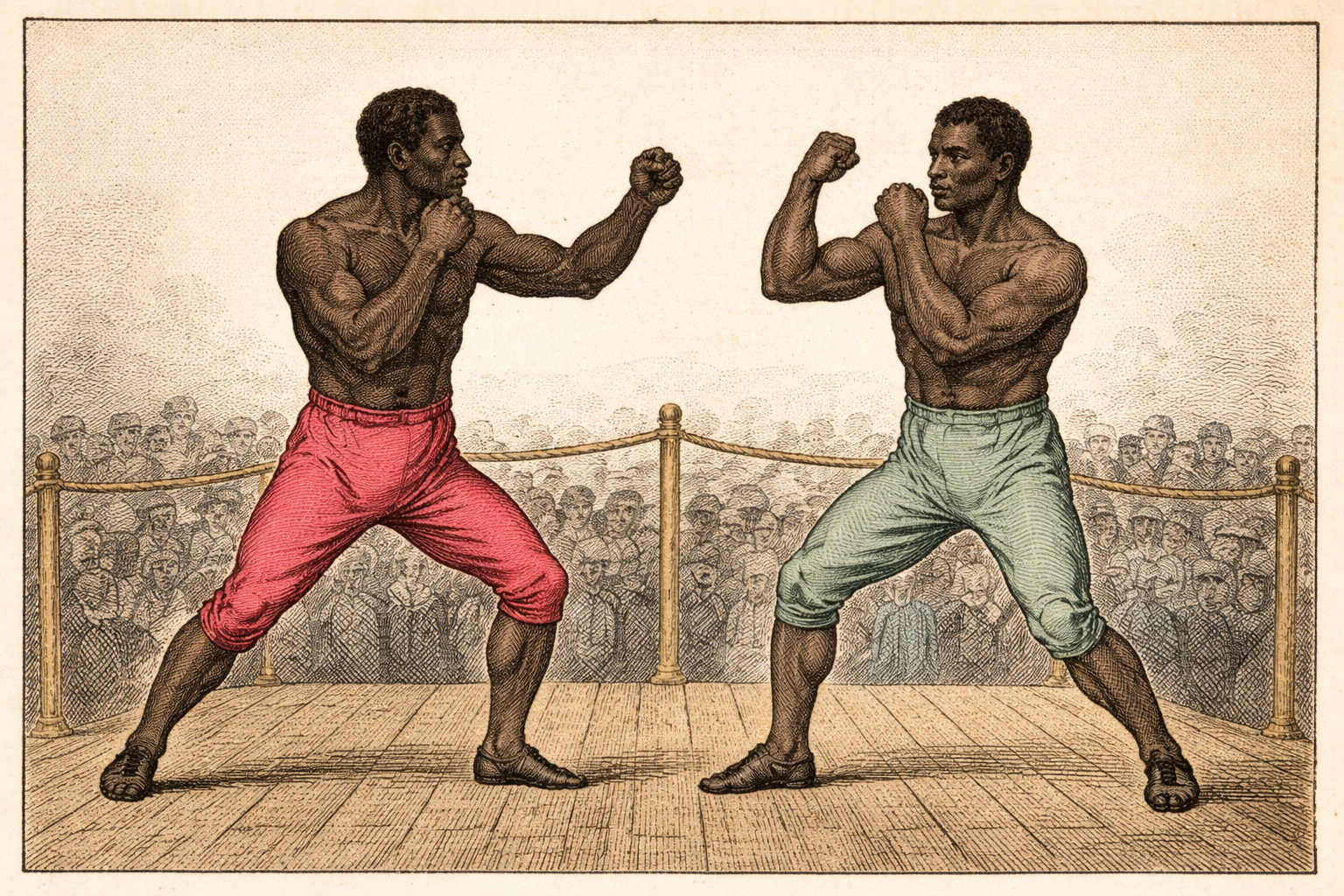

This illustration depicts a ritualized humiliation disguised as opportunity. Powerholders create the contest, define the rules, and reward the survivor — not for excellence, but for endurance and obedience. The violence is outsourced. The spectacle is the point.

Sources

Princeton University, John Witherspoon and Slavery in New Jersey: https://slavery.princeton.edu/stories/john-witherspoon